Programming computers these days is rather simple. Don’t believe me? I do it for a living. While computer programming might not be considered easy to others, it really is just a matter of perspective. Today’s programming tools make the process much easier by abstracting a lot of the core hardware functionality from the programmer. If I were to use an analogy, it would be like the difference between a car having automatic or manual transmission. While it’s possible for everyone to learn to drive a car with manual transmission if they put some effort into it, today’s technology and advances in modern automatic transmissions makes it more convenient to simply go with the automatic. There is simply no substantial benefit to buying a car with manual transmission unless you enjoy the unique experience and fine control of continuously shifting the vehicle while driving. The same goes with computer programming over the past several decades.

I was exposed to home computers early in their existence, back in the ‘ol 8-bit days of Commodore, Radio Shack, and Apple computers. Back then, programming was generally difficult for the masses. People simply did not have a full understanding of what it took to make computers do the things they did. Programmers had to train themselves extensively and those who learned their computer architecture at the hardware level had a tendency to become the most successful software authors.

To learn the hardware extensively, you had to become familiar with a number format called Hexadecimal. Without going into too much detail, hexadecimal, or “hex”, was used to represent the basic binary architecture of a computer in an easy to address (alpha)numerical format. Computers only understand binary numbers comprising of 1’s and 0’s. For example, the number 53 would look like ‘00110101’ in binary. Now try to remember all of the possible combinations of binary available in an 8-bit home computer that could access 65,535 bytes of memory. Memory location 37844 would be ‘1001001111010100’ to the computer.

Sometimes it’s in the best interest of the programmer to be able to reference computer data by binary instead of its decimal equivalent. So, instead of using a bunch of 1’s and 0’s, hex notation can be used. Hex uses not only the digits 0-9 like in decimal numbers, but adds the letters A-F to comprise a range of 16 values per numerical placeholder. What makes this so useful is that hex numbers break down binary numbers in groups of four, yet still maintain the binary reference. In binary, ‘0000’ is the same as the decimal digit ‘0’, ‘0001’ is 1, ‘0010’ is 2, … ‘1001’ is 9, ‘1010’ is A, up to ‘1111’, which is F. Now, the binary number listed above for 37844 can be broken down into groups of four and represented as:

1001 = 9

0011 = 3

1101 = D

0100 = 4

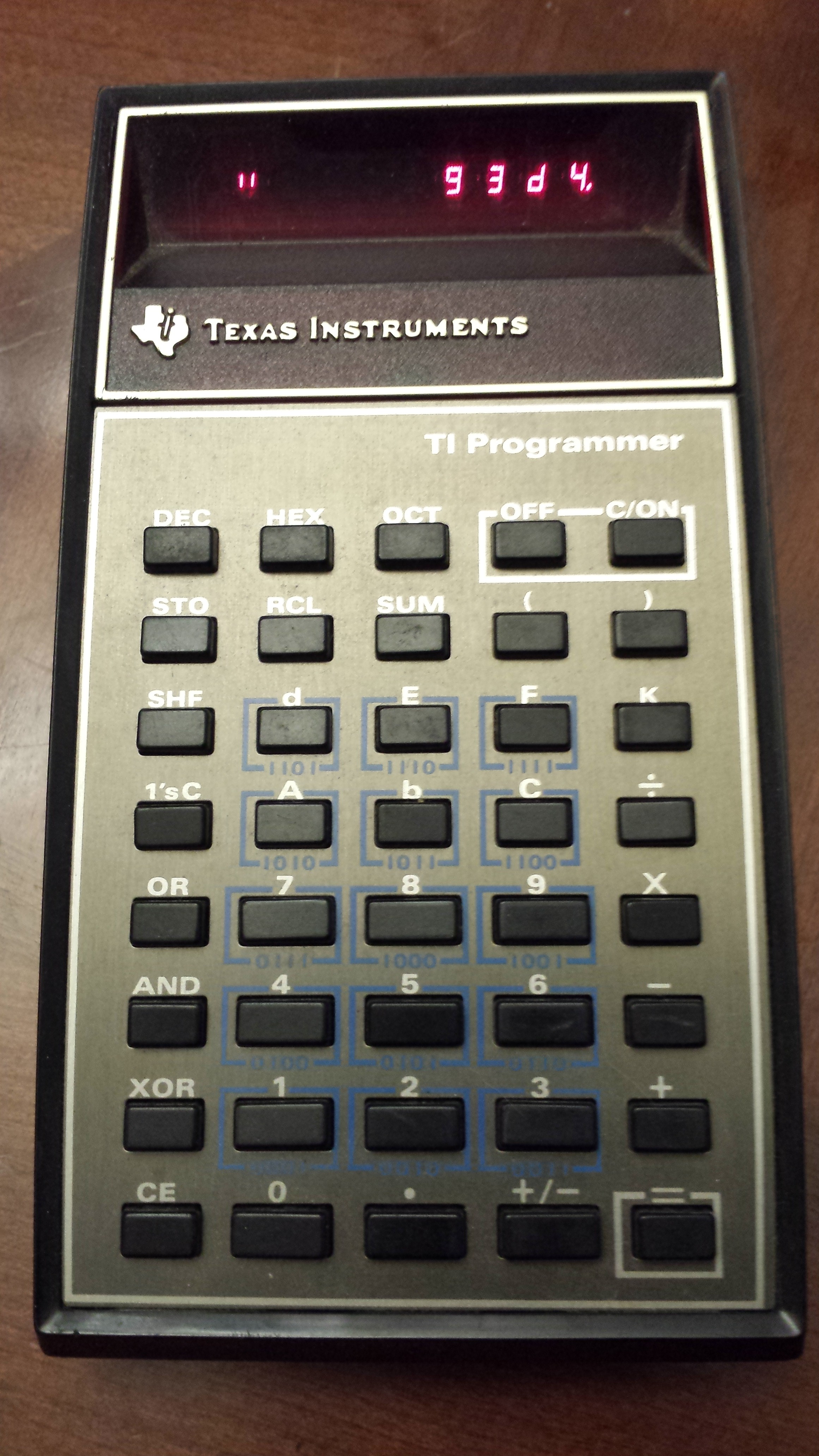

…or ’93D4′ in hexadecimal. Hence, 37844 is the same as ‘1001001111010100’ is the same as ’93D4′

OK. Now that the impromptu computer theory was presented, what does it all have to do with the TI Programmer calculator? Well, back in it’s heyday, when you needed to do some quick number conversions from decimal to hex or vice versa, you just didn’t ‘alt-tab’ to a calculator program on your PC. You needed to use an external reference. The TI Programmer was a very useful external reference.

With the TI Programmer, you could enter a hex number in its proper format and then press one button to turn it into its decimal equivalent. Many computer reference manuals at the time had all of their memory addresses listed in hex notation. Unless they provided a decimal alternative for the address, it was up to you to convert it. The TI Programmer made it easy to do so.

For those who programmed in Assembly Language, you were always using hex number references. At the same time, you still needed to deal with decimal equivalents of those numbers to make sense and manage your program functionality. The TI Programmer made your life much easier, too.

So what is the TI Programmer like?

The TI Programmer is a 40 button handheld calculator in the same style as other TI calculators at the time, namely the TI-57 Programmable calculator and the popular TI-30 Scientific calculator. Like the TI-30, it runs on a single 9-volt battery which fits in an oversized compartment. The compartment is large because it can also use an optional rechargeable battery pack.

The calculator operates as a normal four function calculator with memory and algebraic grouping (parenthesis) capabilities. However, it does those functions in any of the user selectable number modes: Base-10 (Decimal), Base-8 (Octal), and Base-16 (Hex). Just choose the desired mode and perform your calculations as needed, making sure you use the appropriate number notation for that mode.

You can also use the calculator to convert between the available number bases. To convert a Decimal number to Hex, make sure Decimal mode is on (as indicated by the lack of ‘tick marks’ on the left side of the display, enter your decimal number, then press HEX to see the converted number. The left hand of the display shows a single tick mark if you are in Octal mode and a double tick mark in Hex mode.

This isn’t a calculator which would be a “daily user” for anybody who is not regularly working with the number bases it supports. But for a computer programmer, it could very well be one of the most handy calculators back in its day. Heck, I even find myself grabbing it from time to time THESE days.

One other feature this calculator has, due to the nature of LED displays being quick to deplete batteries, is the “battery save mode.” After several seconds of non use, the display turns off except for a sequential display of a decimal point moving across the screen. When this happens, the only power being used by the display is the amount of power it takes to drive a single tiny LED dot, which is not much.